Heartburn’s Hidden Cancer Risk: What You Need to Know

Understanding the link between chronic heartburn and esophageal cancer

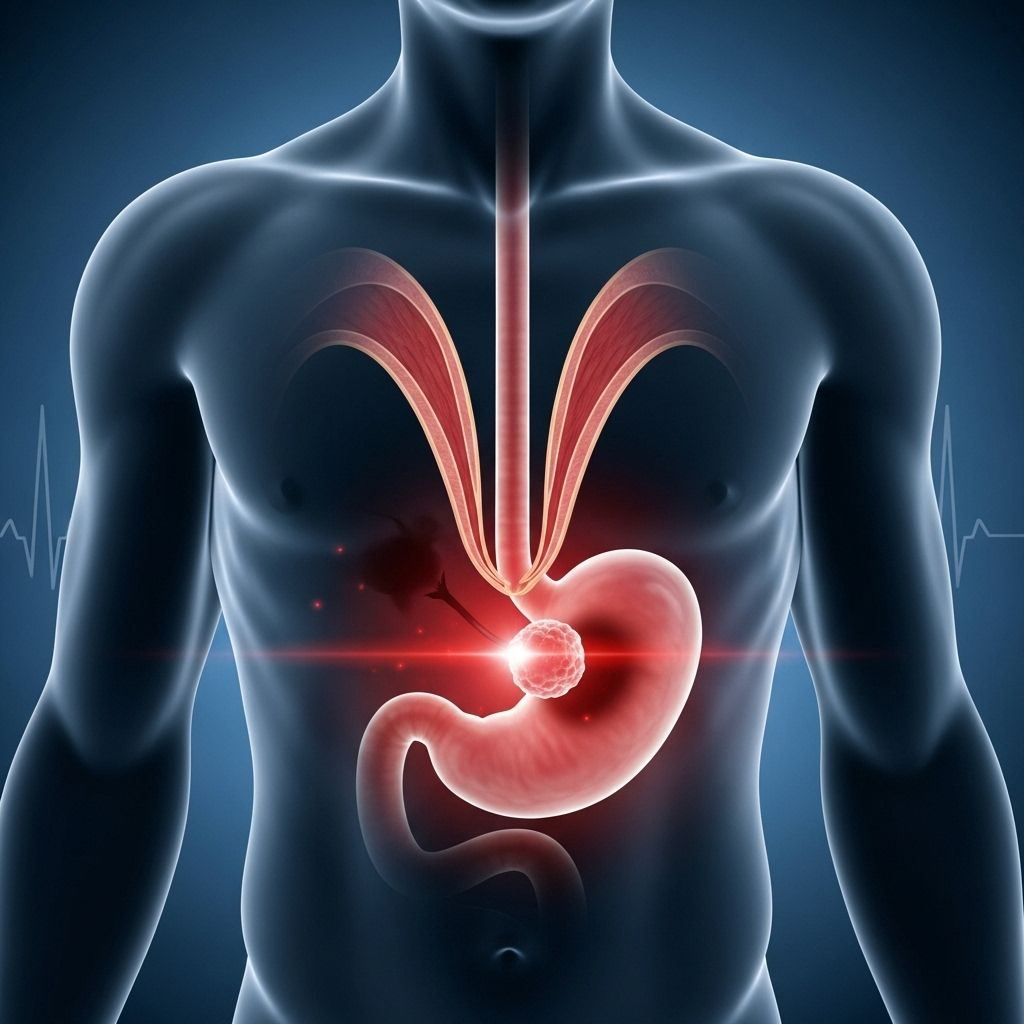

Heartburn is an uncomfortable burning sensation in the chest that most people experience occasionally after eating spicy foods or large meals. While occasional heartburn is generally harmless, persistent or frequent heartburn may signal a more serious underlying condition that could potentially lead to cancer. Understanding the connection between chronic heartburn and esophageal cancer is crucial for early detection and prevention.

Understanding the Connection Between Heartburn and Cancer

Many people dismiss frequent heartburn as a minor inconvenience, but medical experts warn that this symptom deserves serious attention. Chronic heartburn is often a sign of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a condition where stomach acid regularly flows back into the esophagus, the tube connecting your mouth to your stomach. While heartburn itself is not the same as GERD, it represents one of the most common and recognizable symptoms of this digestive disorder.

The relationship between heartburn and cancer risk is not direct but follows a progressive pathway. When acid from the stomach repeatedly flows into the esophagus, it causes irritation and damage to the esophageal lining. Unlike the stomach, which has a protective mucous layer designed to withstand acidic conditions, the esophagus lacks this natural defense mechanism. Over time, this persistent acid exposure can trigger cellular changes in the esophageal tissue, potentially setting the stage for more serious complications.

What is GERD and Why Does It Matter?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease represents a chronic digestive disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. The condition occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter, a ring of muscle at the junction between the esophagus and stomach, becomes weakened or relaxes inappropriately. This muscular valve normally acts as a one-way door, allowing food and liquids to enter the stomach while preventing stomach contents from flowing backward.

When this sphincter malfunctions, stomach acid and bile can regularly escape into the esophagus, causing the characteristic burning sensation known as heartburn. People who experience heartburn more than twice a week should consult a gastroenterologist for proper evaluation and management. This frequency indicates that the condition has moved beyond occasional discomfort into the realm of chronic disease requiring medical attention.

Several factors can compromise the functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter. Lifestyle choices such as consuming caffeine, alcohol, and smoking can relax this muscle and increase reflux episodes. Physical conditions including obesity, pregnancy, and hiatal hernias also contribute to sphincter dysfunction. Interestingly, stress plays a significant role as well. When the body produces elevated levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, it can cause the sphincter to relax, which explains why many people experience increased heartburn during periods of high stress.

The Progressive Path: From GERD to Barrett’s Esophagus

Long-term acid exposure to the esophageal lining initiates a remarkable but concerning process called metaplasia. In this cellular transformation, the normal squamous cells lining the esophagus gradually change into cells that more closely resemble those found in the stomach or intestine. This adaptation represents the body’s attempt to protect itself from ongoing acid exposure by creating tissue better suited to an acidic environment.

This precancerous condition is known as Barrett’s esophagus, named after the British surgeon Norman Barrett who first described it in the 1950s. Barrett’s esophagus represents a critical warning sign in the progression toward esophageal cancer. Research indicates that patients with Barrett’s esophagus face approximately a one percent annual risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. While this percentage may seem small, it represents an absolute and additive risk, meaning each year with Barrett’s esophagus carries a fresh chance of cancer development.

The transformation from normal esophageal tissue to Barrett’s esophagus happens gradually, often over many years of chronic acid exposure. During this process, cell division can go awry, and when these abnormal cells accumulate, tumors can develop. These malignancies may initially remain confined to the esophagus but can eventually spread to lymph nodes and other organs including the lungs, liver, and brain.

Risk Factors for Developing Barrett’s Esophagus

Understanding who faces the highest risk for Barrett’s esophagus helps identify individuals who need closer monitoring and more aggressive preventive measures. Medical research has identified several key demographic and lifestyle factors that significantly increase the likelihood of developing this precancerous condition.

Gender plays a substantial role, with men being three to four times more likely than women to develop Barrett’s esophagus. The reasons for this gender disparity remain under investigation, but hormonal differences and varying patterns of fat distribution may contribute to the increased male susceptibility.

Age represents another critical factor, with individuals over 50 facing elevated risk. The cumulative effect of years of acid exposure, combined with age-related changes in the esophageal sphincter and tissue resilience, contributes to this increased vulnerability in older adults.

Ethnicity also influences risk, with Caucasian individuals showing higher rates of Barrett’s esophagus compared to other ethnic groups. Researchers continue investigating the genetic and environmental factors that might explain these racial differences in disease prevalence.

Obesity, particularly abdominal obesity, represents one of the most significant modifiable risk factors. Excess weight around the midsection increases pressure on the stomach, forcing acid upward into the esophagus. Additionally, fat tissue produces inflammatory substances that may contribute to cellular changes in the esophageal lining. The rising rates of obesity in many countries correlate closely with increasing incidence of chronic heartburn and related cancers.

Smoking damages the esophageal lining directly while also relaxing the lower esophageal sphincter, creating a double threat for those who use tobacco products. The chemicals in tobacco smoke can also interfere with saliva production, which normally helps neutralize acid in the esophagus.

Family history matters significantly in Barrett’s esophagus risk. Individuals with close relatives who have been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer face substantially higher risk themselves, suggesting important genetic components to disease susceptibility.

Warning Signs: Recognizing Symptoms of Esophageal Cancer

When Barrett’s esophagus progresses to esophageal cancer, several symptoms may emerge, though unfortunately these signs often appear only after the disease has advanced. Early-stage esophageal cancer frequently produces no symptoms, which makes screening for high-risk individuals especially important.

Difficulty swallowing, medically termed dysphagia, represents one of the most common symptoms of esophageal cancer. Patients typically first notice problems with solid foods, with the difficulty progressively worsening over time. As the tumor grows, it narrows the esophageal passage, making it increasingly challenging for food to pass through.

Unintended weight loss occurs frequently in esophageal cancer patients, resulting both from swallowing difficulties that reduce food intake and from the metabolic demands of the growing tumor. Weight loss of more than 10 pounds without trying should always prompt medical evaluation.

Chest pain or discomfort, particularly behind the breastbone, may indicate esophageal cancer. This pain differs from typical heartburn and may feel like pressure, burning, or aching that persists regardless of eating or taking antacids.

Persistent coughing or hoarseness can develop when esophageal tumors irritate nerves or when food and liquid enter the windpipe due to swallowing problems. These respiratory symptoms may be mistaken for other conditions, delaying cancer diagnosis.

Worsening heartburn or indigestion that doesn’t respond to usual treatments may signal cancer development. While these symptoms alone don’t confirm cancer, their persistence despite appropriate therapy warrants further investigation.

Additional Risk Factors for Cancer Progression

Research has identified several factors beyond Barrett’s esophagus that influence the likelihood of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. Studies involving hundreds of patients have revealed important patterns that can help identify those at highest risk.

Caffeine consumption shows a dose-dependent relationship with cancer risk. Patients who consume caffeine weekly, daily, or multiple times daily face progressively higher risks of progression from Barrett’s esophagus to cancer. Caffeine relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter and increases stomach acid production, creating conditions favorable for ongoing esophageal damage.

The presence of low-grade dysplasia, which represents early cellular abnormalities detected on biopsy, significantly increases cancer risk. Patients with dysplasia require more frequent surveillance and may benefit from preventive treatments to remove abnormal tissue before cancer develops.

Interestingly, patients with a history of colonic adenomas, precancerous polyps found in the colon, also show increased risk of esophageal cancer. This connection suggests shared genetic or environmental factors that promote abnormal cell growth in different parts of the digestive system.

Protective Factors and Prevention Strategies

While understanding risk factors is important, knowing what can protect against cancer progression offers hope for prevention. Medical research has identified several medications and lifestyle factors that appear to reduce the risk of developing esophageal cancer in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

Statin medications, commonly prescribed to lower cholesterol, demonstrate remarkable protective effects. Studies show that regular statin use reduces the risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or cancer by approximately 49 percent. These drugs appear to have anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties beyond their cholesterol-lowering effects.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), medications typically used to treat depression and anxiety, show even more impressive protective effects, reducing cancer risk by about 61 percent. Researchers are still working to understand the mechanisms behind this protection, but the findings suggest potential for repurposing these common medications for cancer prevention.

Supplemental calcium and vitamin D also trend toward protective effects. These nutrients play important roles in regulating cell growth and differentiation, which may explain their beneficial impact on preventing cancerous changes in the esophagus.

Maintaining a healthy weight represents one of the most important modifiable factors for reducing esophageal cancer risk. Weight loss, particularly reduction of abdominal fat, decreases pressure on the stomach and reduces acid reflux episodes. Even modest weight loss of 5 to 10 percent of body weight can significantly improve GERD symptoms.

Eliminating tobacco use is crucial, as smoking not only increases Barrett’s esophagus risk but also promotes progression to cancer. Quitting smoking at any age provides substantial health benefits and reduces cancer risk over time.

The Changing Landscape of Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal adenocarcinoma represents one of the fastest-growing solid cancers in developed countries, with incidence rates rising dramatically over the past several decades. This trend parallels the increasing prevalence of obesity and GERD in these populations, supporting the strong connection between chronic acid reflux and cancer development.

The rising rates of this cancer are particularly concerning because esophageal adenocarcinoma is difficult to treat and carries a poor prognosis. Currently, no effective screening techniques exist for the general population, and most patients receive their diagnosis only after the cancer has reached advanced stages. By this point, treatment options are limited, and life expectancy is typically measured in months rather than years.

Interestingly, some researchers believe the rise in esophageal adenocarcinoma may be partially due to changes in the gut microbiome. The loss of certain bacteria, particularly Helicobacter pylori, which once colonized most human stomachs but has become less common due to improved sanitation and antibiotic use, may have inadvertently increased esophageal cancer risk. H. pylori can reduce stomach acid production, and its decline may have led to higher acid levels that promote reflux and subsequent cancer development.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Given the serious potential consequences of chronic heartburn, knowing when to consult a healthcare provider is essential. Anyone experiencing heartburn more than twice weekly should undergo evaluation by a gastroenterologist. This frequency suggests GERD rather than occasional reflux, and proper management can prevent progression to Barrett’s esophagus.

Individuals with long-standing GERD, particularly those with multiple risk factors such as obesity, smoking, or family history, should discuss surveillance options with their doctors. Regular endoscopic examinations allow physicians to detect Barrett’s esophagus early and monitor for dysplastic changes that might precede cancer.

Any new or worsening symptoms, including difficulty swallowing, unexplained weight loss, persistent chest pain, or heartburn that no longer responds to medications, require prompt medical evaluation. These warning signs may indicate cancer development and need immediate investigation.

Patients already diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus need regular monitoring based on the degree of dysplasia present. Those without dysplasia typically undergo surveillance endoscopy every three to five years, while those with low-grade dysplasia require more frequent examinations every six to twelve months. High-grade dysplasia often prompts consideration of endoscopic treatment to remove abnormal tissue before invasive cancer develops.

Current Treatment and Management Approaches

Managing the spectrum from GERD to Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal cancer requires a multifaceted approach tailored to each patient’s specific situation. For GERD, treatment typically begins with lifestyle modifications including weight loss, dietary changes, elevation of the head of the bed, and avoidance of trigger foods and beverages.

Medications play a central role in GERD management. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) effectively reduce stomach acid production and provide symptom relief for most patients. However, eliminating acid reflux with medication does not heal Barrett’s esophagus, and the changed cells do not revert to normal esophageal characteristics. This limitation underscores the importance of preventing Barrett’s esophagus from developing in the first place through early and aggressive GERD management.

For patients with Barrett’s esophagus, surveillance strategies focus on detecting dysplasia before cancer develops. When dysplasia is found, several treatment options exist to remove abnormal tissue. Radiofrequency ablation uses heat energy to destroy precancerous cells, while endoscopic mucosal resection allows physicians to remove larger areas of abnormal tissue. These procedures can effectively eliminate dysplasia and reduce cancer risk when performed in appropriate patients.

Unfortunately, treatment options for established esophageal cancer remain limited and challenging. Surgery to remove part or all of the esophagus represents the primary curative approach for early-stage disease, but this operation carries significant risks and complications. Advanced cancers may require chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or combinations of these treatments, though outcomes remain poor compared to many other cancer types.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How common is esophageal cancer in people with chronic heartburn?

A: While most people with chronic heartburn will not develop esophageal cancer, the risk increases significantly compared to those without GERD. Approximately 10-15% of people with chronic GERD develop Barrett’s esophagus, and of those, about 0.5-1% per year progress to esophageal cancer. The cumulative risk over many years makes monitoring and prevention crucial for high-risk individuals.

Q: Can taking antacids prevent esophageal cancer?

A: Antacids and acid-suppressing medications like proton pump inhibitors can effectively control heartburn symptoms and reduce acid exposure to the esophagus. However, once Barrett’s esophagus develops, these medications cannot reverse the cellular changes. Early and consistent treatment of GERD may help prevent Barrett’s esophagus from developing initially, but cannot guarantee cancer prevention once precancerous changes have occurred.

Q: Are there any dietary changes that can reduce esophageal cancer risk?

A: Yes, several dietary modifications can help reduce acid reflux and potentially lower cancer risk. Avoiding trigger foods such as spicy dishes, citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate, and fatty foods can minimize reflux episodes. Limiting caffeine and alcohol consumption also helps, as both substances relax the lower esophageal sphincter. Eating smaller meals, avoiding eating within three hours of bedtime, and maintaining a healthy weight through balanced nutrition all contribute to better esophageal health.

Q: Should everyone with heartburn get screened for Barrett’s esophagus?

A: Not everyone with occasional heartburn needs screening, but individuals with chronic GERD lasting more than five years, especially those with multiple risk factors like obesity, male gender, age over 50, Caucasian ethnicity, smoking history, or family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer, should discuss screening with their healthcare provider. The decision should be individualized based on each person’s specific risk profile.

Q: What is the survival rate for esophageal cancer?

A: Esophageal cancer survival rates vary significantly depending on the stage at diagnosis. For localized cancer that hasn’t spread beyond the esophagus, the five-year survival rate is approximately 47%. However, once the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant organs, survival rates drop considerably. This stark difference emphasizes the critical importance of early detection through surveillance of high-risk patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

Q: Can Barrett’s esophagus be reversed?

A: Complete reversal of Barrett’s esophagus through medication alone is rare. The cellular changes that define Barrett’s esophagus generally persist even with excellent acid control using proton pump inhibitors. However, endoscopic ablation treatments can successfully destroy Barrett’s tissue and allow normal esophageal lining to regenerate in many cases. These procedures are typically recommended for patients with dysplasia or those at particularly high risk for cancer progression.

Read full bio of medha deb