Treacher Collins, Nager & Miller Syndromes: Complete Guide

Understanding rare craniofacial syndromes and their comprehensive treatment

Craniofacial syndromes represent a complex group of genetic conditions that affect the development of the skull and facial structures. Among these rare disorders, Treacher Collins syndrome, Nager syndrome, and Miller syndrome stand out as conditions that require specialized multidisciplinary care and comprehensive treatment approaches. Understanding these syndromes is essential for families, healthcare providers, and communities to provide optimal support and medical intervention for affected individuals.

Understanding Treacher Collins Syndrome

Treacher Collins syndrome, also known as mandibulofacial dysostosis or Franceschetti-Zwalen-Klein syndrome, is a rare genetic condition that affects the development of bones and tissues in the face. This syndrome occurs in approximately 1 in 50,000 newborns worldwide, making it one of the more common craniofacial syndromes, though still considered rare in the general population.

The condition is caused by genetic mutations that disrupt facial development during pregnancy. About 60% of cases result from new spontaneous mutations not inherited from either parent, while the remaining cases involve inheritance of an abnormal gene from an affected parent. The syndrome follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning only one copy of the altered gene is necessary to cause the condition.

Characteristic Features of Treacher Collins Syndrome

Individuals with Treacher Collins syndrome display a range of facial characteristics that vary significantly in severity from person to person. The most commonly observed features include a very small lower jaw and chin, known medically as micrognathia, and an undersized upper jaw called maxillary hypoplasia. These jaw abnormalities often create a distinctive facial profile and can contribute to functional challenges.

Cheekbone underdevelopment represents another hallmark feature, giving the mid-face a flattened appearance. The eyes typically slant downward at the outer corners, and many individuals have a notch or gap in the lower eyelids called a coloboma. Ear abnormalities are particularly common, ranging from small, unusually formed ears (microtia) to complete absence of external ear structures. These ear differences often lead to hearing difficulties, affecting at least half of all individuals with the syndrome.

Approximately 25% of children with Treacher Collins syndrome are born with a cleft palate, an opening in the roof of the mouth that requires surgical repair. Some individuals also experience severe breathing difficulties due to narrowed airways, particularly during infancy. Despite these significant physical challenges, people with Treacher Collins syndrome typically have normal intelligence and cognitive development.

Nager Syndrome: A Related Craniofacial Condition

Nager syndrome, also called Nager acrofacial dysostosis, shares several features with Treacher Collins syndrome but includes additional limb abnormalities that distinguish it as a separate condition. This extremely rare syndrome affects facial development similarly to Treacher Collins but extends its impact to the arms, hands, and sometimes legs.

The facial characteristics of Nager syndrome closely mirror those seen in Treacher Collins syndrome, including underdeveloped cheekbones, a small lower jaw, downward-slanting eyes, and ear malformations. However, the defining feature of Nager syndrome is the presence of limb differences, particularly affecting the thumbs and forearms. Individuals may have absent or underdeveloped thumbs, shortened forearms due to absent or underdeveloped radius bones, and occasionally differences in leg development.

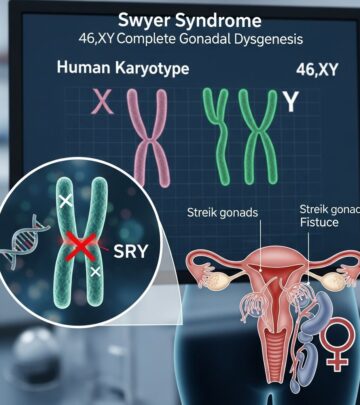

Genetic Basis and Inheritance Patterns

The genetic causes of Nager syndrome are more complex and less well understood than those of Treacher Collins syndrome. Most cases appear to occur sporadically as new mutations, though some familial cases have been documented. Researchers have identified mutations in the SF3B4 gene in some individuals with Nager syndrome, though not all cases can be explained by changes in this gene, suggesting genetic heterogeneity.

The limb abnormalities in Nager syndrome can significantly impact hand function and fine motor skills, requiring specialized occupational therapy and potentially reconstructive surgery. Children with Nager syndrome face similar breathing, feeding, and hearing challenges as those with Treacher Collins syndrome, but with the added complexity of managing upper limb differences.

Miller Syndrome: Understanding the Rarest Form

Miller syndrome, also known as postaxial acrofacial dysostosis, represents the rarest of these three craniofacial conditions. Like Nager syndrome, Miller syndrome combines facial underdevelopment with limb abnormalities, but the pattern of limb involvement differs distinctly.

Individuals with Miller syndrome exhibit severe micrognathia, malar hypoplasia (underdeveloped cheekbones), and eyelid colobomas similar to the other syndromes. However, Miller syndrome typically involves the outer (postaxial) portions of the limbs, particularly affecting the fifth fingers and toes, which may be shortened or absent. Cup-shaped ears and cleft lip or palate occur more frequently in Miller syndrome than in the other conditions.

Genetic Understanding and Diagnosis

Miller syndrome follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, distinguishing it from the autosomal dominant Treacher Collins syndrome. This means both parents must carry one copy of the mutated gene for a child to be affected. Mutations in the DHODH gene have been identified as the cause of Miller syndrome. This gene provides instructions for an enzyme involved in producing pyrimidines, essential components of DNA and RNA.

The severe nature of Miller syndrome often results in significant medical complications, and affected individuals require intensive multidisciplinary care from birth. The combination of severe micrognathia with respiratory compromise makes early intervention critical for survival and quality of life.

Diagnostic Approaches for Craniofacial Syndromes

Diagnosis of these craniofacial syndromes typically begins with careful physical examination shortly after birth or within the first year of life. Healthcare providers familiar with these conditions can often recognize characteristic facial features immediately. However, mild cases, particularly of Treacher Collins syndrome, may not be diagnosed until later in childhood or even adulthood.

Advanced imaging techniques play a crucial role in comprehensive assessment. Three-dimensional CT scans provide detailed visualization of bone structures, helping clinicians understand the extent of skeletal abnormalities and plan surgical interventions. These imaging studies reveal the precise anatomy of underdeveloped facial bones, guiding treatment decisions.

Genetic testing confirms clinical diagnoses and provides valuable information for family planning. DNA analysis can identify specific mutations in genes associated with these syndromes. For Treacher Collins syndrome, testing examines genes including TCOF1, POLR1C, and POLR1D. Nager syndrome testing may include SF3B4 gene analysis, while Miller syndrome diagnosis involves DHODH gene sequencing.

Prenatal diagnosis through ultrasound may detect severe cases during pregnancy, though many cases are not apparent until birth. Families with a known history of these conditions can pursue prenatal genetic testing if specific mutations have been identified in family members.

Comprehensive Treatment Strategies

There is no cure for these craniofacial syndromes, but comprehensive treatment can dramatically improve function, appearance, and quality of life. Treatment requires coordinated care from a multidisciplinary craniofacial team including geneticists, plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, audiologists, speech pathologists, orthodontists, and other specialists.

Early Intervention and Airway Management

The most urgent priority in newborns with these syndromes is establishing a safe airway. Severe micrognathia can cause the tongue to fall backward, blocking the airway—a condition called glossoptosis. Initial management may involve specialized positioning techniques that help keep the airway open. Some infants require more intensive interventions.

Mandibular distraction osteogenesis represents a surgical technique that gradually lengthens the lower jaw. Surgeons make cuts in the jawbone and insert special devices that slowly separate the bone segments over several weeks, allowing new bone to form in the gap. This procedure, typically performed during infancy, simultaneously addresses breathing problems and feeding difficulties while avoiding the need for tracheostomy in many cases.

For infants with severe airway obstruction that cannot be managed through jaw surgery or positioning, tracheostomy may be necessary. This procedure creates an opening in the windpipe, allowing the child to breathe through a tube inserted into the neck. While this represents a significant intervention, it can be lifesaving and is often temporary, with the tracheostomy removed once the child’s airway has been adequately enlarged through subsequent surgeries.

Feeding Support and Nutritional Management

Children with these syndromes frequently experience feeding difficulties due to small jaw size, cleft palate, and swallowing problems. Specialized feeding techniques and modified bottles can help infants receive adequate nutrition during the early months. Lactation consultants and feeding specialists work closely with families to develop effective feeding strategies.

Regular monitoring of weight gain and growth is essential. Dietitians provide guidance on caloric needs and may recommend fortified formulas or supplemental nutrition. In cases where oral feeding proves inadequate, gastrostomy tube (G-tube) placement may be necessary to ensure proper nutrition. This feeding tube, inserted directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall, provides a reliable route for nutrition and medications while the child develops oral feeding skills.

Hearing Rehabilitation

Hearing loss affects the majority of children with these craniofacial syndromes, typically due to malformed ear canals and middle ear structures. Conductive hearing loss, caused by problems transmitting sound through the outer and middle ear, is most common and often responds well to hearing aids.

Bone-anchored hearing aids (BAHA) represent an excellent option for many children with these conditions. These devices bypass the outer and middle ear by transmitting sound vibrations directly through the skull bone to the inner ear. Early implementation of hearing aids is crucial for normal speech and language development, as even mild hearing loss during critical developmental periods can significantly impact communication skills.

Regular audiological assessments track hearing status and ensure appropriate amplification as children grow. Some individuals may benefit from surgical reconstruction of the ear canal or middle ear structures, though the timing and feasibility of such procedures depend on individual anatomy.

Surgical Reconstruction: A Staged Approach

Reconstructive surgery for craniofacial syndromes follows a carefully planned, age-based approach that considers both functional needs and facial growth patterns. The timing of various procedures is strategically chosen to provide maximum benefit while minimizing interference with natural development.

Cleft Palate Repair

For children born with cleft palate, surgical closure typically occurs around 9 to 18 months of age. This timing allows sufficient growth for surgical repair while occurring early enough to support normal speech development. Cleft palate repair closes the opening in the roof of the mouth, separating the oral and nasal cavities and enabling proper speech, feeding, and middle ear function.

Eyelid Reconstruction

Lower eyelid colobomas require surgical correction to protect the eyes from drying and injury. These procedures may be performed during infancy or early childhood, depending on severity. Surgeons reconstruct the missing eyelid tissue using grafts and specialized techniques to restore normal eyelid closure and protect corneal health.

Midface and Cheekbone Reconstruction

Reconstruction of underdeveloped cheekbones and midface structures typically occurs during school-age years or later, after significant facial growth has occurred. These complex procedures may involve bone grafts taken from the ribs, hip, or skull to build up deficient areas. Fat grafting can also enhance facial contours and improve appearance.

Some surgeons use distraction osteogenesis techniques to advance the entire midface forward, improving both appearance and function. These procedures gradually reposition facial bones over weeks or months, allowing soft tissues to adapt to the new skeletal framework.

Jaw Surgery in Adolescence

Orthognathic surgery, performed during teenage years after facial growth is complete, addresses remaining jaw discrepancies. Surgeons may reposition the upper jaw, lower jaw, or both to achieve proper bite alignment and facial balance. These procedures dramatically improve both appearance and function, enabling better chewing and speech.

Orthodontic treatment usually begins several years before jaw surgery and continues afterward to achieve optimal dental alignment. The combination of orthodontics and orthognathic surgery can transform facial appearance and significantly enhance quality of life.

Ear Reconstruction

For children with significant ear malformations, reconstruction typically begins around age 6 to 8 years, when the ears have reached approximately 85% of adult size and rib cartilage is sufficient for grafting. Ear reconstruction is a complex, multi-stage process that may span several years.

Surgeons can build new ear structures using the patient’s own rib cartilage, carved and shaped to create a natural-appearing ear framework. Alternative approaches include prosthetic ears attached with surgical implants or adhesives. The choice of technique depends on available tissue, patient preference, and individual anatomy.

Speech and Language Development

Speech therapy plays a vital role in the comprehensive care of children with craniofacial syndromes. Hearing loss, abnormal oral structures, and cleft palate all impact speech development. Early intervention with speech-language pathologists helps children develop communication skills and addresses articulation problems, resonance disorders, and language delays.

Speech pathologists also assess and treat swallowing difficulties (dysphagia), which can affect safety during eating and drinking. Video swallow studies may be performed to evaluate swallowing function and guide treatment recommendations. Therapy focuses on improving oral motor skills, teaching compensatory strategies, and ensuring safe, efficient feeding.

Psychosocial Support and Quality of Life

Living with a craniofacial difference presents unique psychosocial challenges. Children may face staring, questions, or bullying related to their appearance. Family support, counseling, and connection with others who have similar conditions can help build resilience and positive self-esteem.

Many craniofacial centers offer psychological services as part of comprehensive care. Mental health professionals help families cope with diagnosis, navigate treatment decisions, and address emotional challenges. Support groups provide opportunities to connect with other families facing similar circumstances.

School-based support is essential. Educational professionals should be informed about the child’s condition, medical needs, and any functional limitations. Children may need accommodations for hearing loss, such as preferential seating or FM systems. Some children benefit from educational sessions that help classmates understand their condition and reduce stigma.

Long-Term Outlook and Adult Care

With comprehensive treatment and support, individuals with these craniofacial syndromes can lead fulfilling, productive lives. Normal intelligence in Treacher Collins syndrome means educational and career opportunities are unlimited. Advances in surgical techniques continue to improve outcomes, and many adults with these conditions achieve excellent functional results and aesthetic appearance.

Transition to adult healthcare requires careful planning. Young adults need ongoing monitoring for potential complications, maintenance of hearing aids or other assistive devices, and access to additional reconstructive procedures if desired. Dental care remains important throughout life, as bite problems and missing teeth may require continued management.

Genetic counseling is important for adults with these conditions who are considering having children. Understanding inheritance patterns helps individuals make informed family planning decisions. Prenatal testing options are available for those who wish to pursue them.

Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research continues to advance understanding of these craniofacial syndromes. Scientists are identifying additional genes involved in facial development, improving diagnostic capabilities, and developing new treatment approaches. Advances in genetic testing enable earlier diagnosis and better understanding of syndrome variability.

Surgical techniques continue to evolve, with less invasive approaches and improved outcomes. Three-dimensional surgical planning using advanced imaging allows surgeons to precisely plan and execute complex reconstructions. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine hold promise for future treatment options.

International registries and research consortia are collecting data on individuals with these rare conditions, enabling studies that would be impossible at single centers. This collaborative research approach accelerates discoveries and improves care for all affected individuals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can Treacher Collins syndrome, Nager syndrome, or Miller syndrome be prevented?

A: These syndromes cannot be prevented as they result from genetic mutations. However, genetic counseling can help families understand inheritance risks. For autosomal dominant conditions like Treacher Collins syndrome, an affected parent has a 50% chance of passing the condition to each child. For autosomal recessive Miller syndrome, carrier parents have a 25% chance with each pregnancy.

Q: How does Treacher Collins syndrome affect life expectancy?

A: With appropriate medical care, particularly early airway management, individuals with Treacher Collins syndrome typically have normal life expectancy. The most critical period is infancy when breathing difficulties pose the greatest risk. Once airway issues are addressed and the child is growing well, long-term survival is excellent.

Q: Will my child with one of these syndromes be able to attend regular school?

A: Yes, most children with these craniofacial syndromes have normal intelligence and can attend mainstream schools. They may need accommodations for hearing loss, such as hearing aids, preferential seating, or assistive listening devices. Some children may miss school for medical appointments and surgeries, requiring educational support to keep up with academics.

Q: How many surgeries will my child need?

A: The number of surgeries varies greatly depending on syndrome severity and individual needs. Some children may undergo 5 to 10 or more procedures throughout childhood and adolescence, while those with milder features may require fewer interventions. Your craniofacial team will develop a personalized surgical plan based on your child’s specific needs.

Q: Is genetic testing necessary if my child clearly has one of these syndromes?

A: While clinical diagnosis is often sufficient for treatment planning, genetic testing provides valuable information for family planning, helps predict disease course, and confirms the specific syndrome. Testing can identify the exact genetic mutation, which is particularly useful if family members want prenatal testing in future pregnancies.

Q: What is the difference between Treacher Collins, Nager, and Miller syndromes?

A: All three syndromes affect facial bone development, but Nager and Miller syndromes also involve limb abnormalities. Treacher Collins affects only the face, Nager syndrome includes thumb and forearm differences, and Miller syndrome affects the outer portions of hands and feet. They also differ in genetic causes and inheritance patterns.

Q: Can adults with these syndromes have additional reconstructive surgery?

A: Yes, many adults choose to undergo additional reconstructive procedures to further refine their appearance or address functional concerns. Rhinoplasty, jaw revision surgery, fat grafting, and other procedures can be performed in adulthood. Advances in surgical techniques mean options continue to improve over time.

Q: Where can I find support and connect with other families?

A: Several organizations provide support for families affected by craniofacial conditions, including Children’s Craniofacial Association, FACES: The National Craniofacial Association, and specific syndrome support groups. Many craniofacial centers also facilitate family connections and support groups. Online communities offer opportunities to connect with families worldwide.

Read full bio of medha deb